After Life: Ricky strikes the right balance

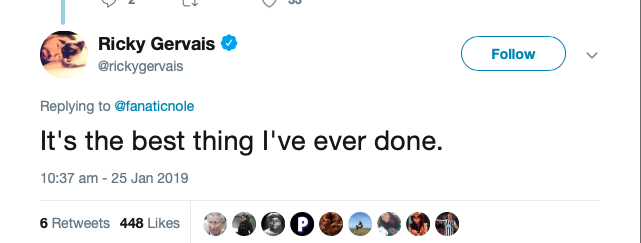

The hype machine has been in danger of overheating these last few weeks, channelling all its efforts into making sure the world is aware that Ricky Gervais has a new series, After Life, streaming on Netflix. Ricky, meanwhile, has spaffed a few more gallons of gas into the machine’s fuel tank by insisting that the show’s the best thing he’s done. Well, he was never going to say it’s a steaming pile of Lee Mack, was he?

Regardless, it’s fighting talk from the man behind such genre game-changers as The Office and Extras. But is he right? Is this his masterpiece? In a word, no. Still, you’ve got to admire the way Gervais balances the brutal with the broad while telling the story of angry, suicidal widower Tony. As the likes of The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, BoJack Horseman and arguably even I’m Alan Partridge have shown, it’s not impossible to find dark but relatable humour in subjects like grief, suicide and depression, but it’s a tough trick to pull off.

And After Life really is broad. The setting is a quiet English coastal town, with the kind of blue skies that only exist in childhood memories and a glorious stretch of sand within moping distance. Ok, there seems to be a mugging problem that the local coppers need to get a handle on sharpish, but it’s hardly Broadchurch. The supporting characters, meanwhile, are so accepting of the appalling way Tony treats them that, at certain points, you’d forgiven for wondering if the show is eventually going to reveal itself as some kind of weird, British seaside version of Westworld.

Here’s what it feels like: you know how Hollyoaks sometimes does a grown up and gritty late night spin off, in which all the regular characters are suddenly swearing and swigging meths inside strip clubs? Well, imagine if Doc Martin, with its idyllic location and grumpy Martin Clunes combo, did the same. Imagine the mildly misanthropic eponymous GP being supercharged into an out of hours, gin-soaked, smack-smoking megabastard. Imagine that and you won’t be a million miles from the tone of After Life. By the way, who wouldn’t want to watch that version of Doc Martin?

The humour itself is also a blend of the malicious and the mainstream. On the one hand you have Tony viciously tearing into friends and strangers alike – his insistence that a 93-year-old victim of one of those previously mentioned muggings couldn’t be scarred for life because of her age, is a highlight. On the other, the gently absurd stories that Tony chases in his job as a local journalist affectionately poke fun at the idiosyncrasies of small town life and just about manage to avoid being patronising.

Away from the laughs, After Life is, of course, a show about pain – Tony’s emotional and existential pain, mainly. However, it’s also about the backside-clenching pain experienced by viewers whenever Tony drops one of his hurtful truth bombs, or truthful hurt bombs – either works.

Gervais, as we know, has a talent for that. Remember the bit in The Office’s Christmas special when irritating, pregnant Anne is verbally taken down by one of the guys from the warehouse, after she complains about him smoking near her? Well, After Life is filled with similar tough-to-watch moments. Except, in this case, it’s even tougher because, while Anne was a wholly unsympathetic character, the victims of Tony’s nihilistic fury rarely deserve it.

Understandably, when the balancing act between broad and brutal is so precarious, you can’t expect to pull it off every time. The way Tony treats drug dependent Julian [Tim Plester] – and the lack of any real repercussion for his actions – feels almost insanely misjudged. And Tony’s handling of the bullying of his young nephew isn’t far behind. Both are simply swept under the forgiving carpet of the show’s ending.

Talking of which, some reviewers have complained that After Life’s climax is mawkish and sickly sweet. Certainly, as Tony’s pain eases and poignancy takes over, the schmaltz arrives by the lorry load. And his realisation that there’s nothing wrong with wishing happiness for good people is hardly revolutionary. But hey, perhaps in divisive times, such simple and, yes, broad messages manage to carry a little more weight.

After Life is streaming now on Netflix. Main pic credit: Natalie Seery.